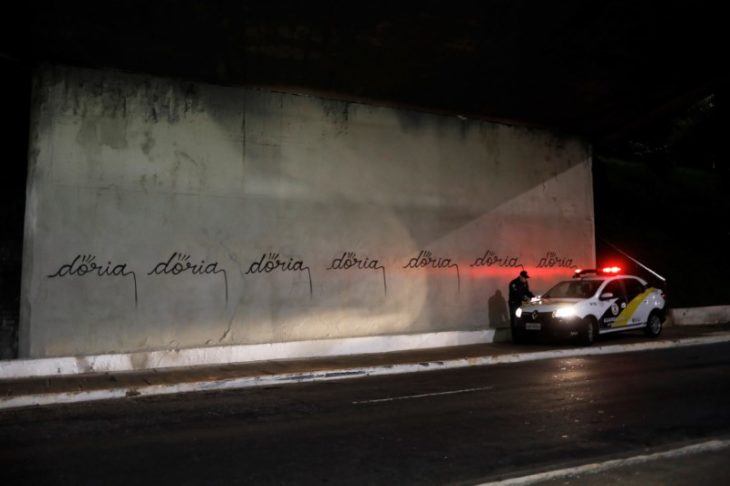

It took Brazilian artist Iaco one minute to whip out a can of spray paint and write “doria” seven times across a gray wall in Sao Paulo.

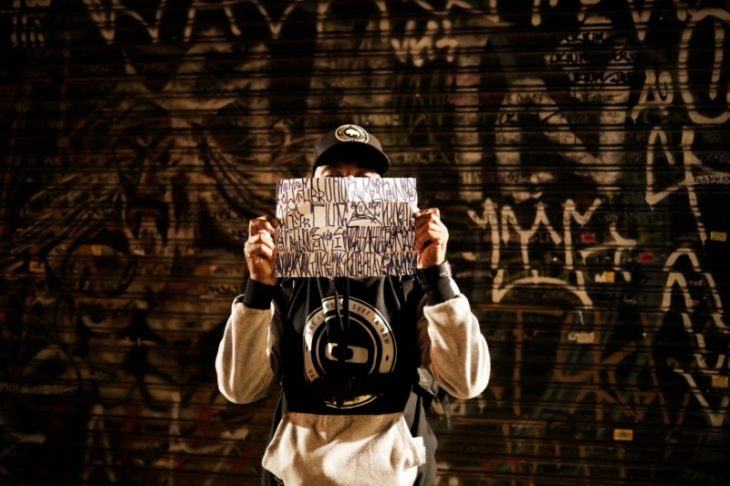

It took four minutes for a police officer to arrive, gun drawn, handcuff Iaco and haul him to the nearest precinct – a swift response to a high-profile provocation in Mayor João Doria’s war on graffiti. A “pichador”, a graffiti artist who tags buildings and landmarks with angular, runic fonts, poses for a photograph in front of a mural of a Brazilian artist “Humanos”, on a street in Sao Paulo, Brazil, April 11, 2017. The two faces on the mural are in reference to a “pichador” (L) and a graffiti artist. REUTERS/Nacho Doce A “pichador”, a graffiti artist who tags buildings and landmarks with angular, runic fonts, paints his personal signature, called “pichacao”, on a wall in Sao Paulo, Brazil, April 21, 2017. REUTERS/Nacho Doce

This was not just any wall.

Weeks before, Doria donned orange overalls and a face mask to help spray gray paint over some 15,000 square meters of street art along that same stretch of Avenida 23 de Maio.

The fate of those murals, commissioned by the prior mayor, has sparked a debate over the world-famous graffiti scene in South America’s biggest city and its place in the cleaner landscape imagined by Doria’s “Pretty City” program.

The mayor has since called the move to repaint that busy avenue too hasty and now insists that his fight is not with the city’s colorful street art but with a style of aggressive tagging known as “pichação.”

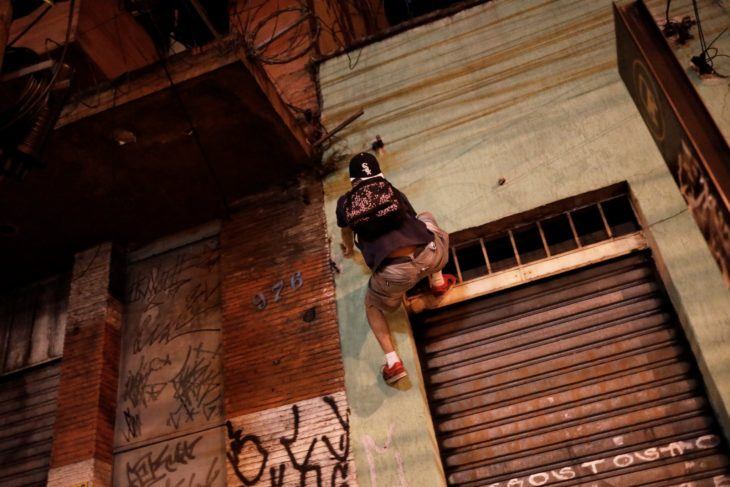

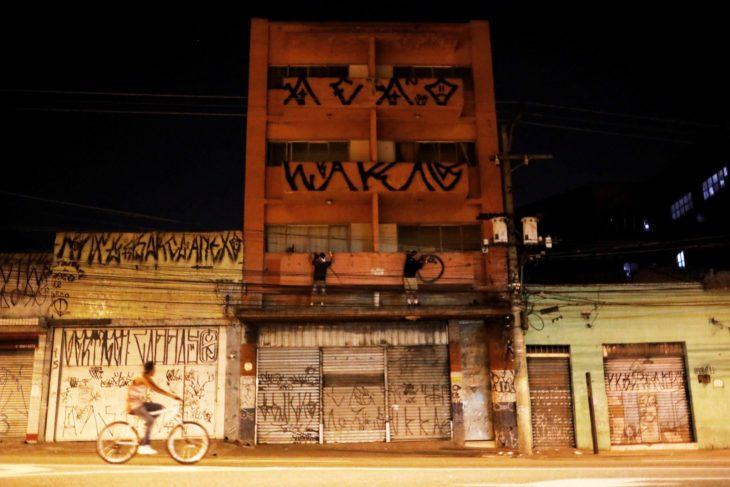

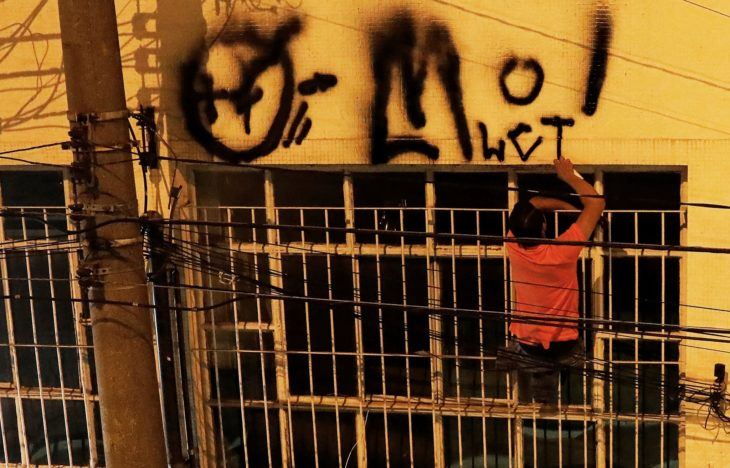

The angular, runic font has conquered swaths of Sao Paulo’s landscape as unseen street artists scale buildings and landmarks with paint rollers and spray cans in hand, drawing the ire of many who embrace other forms of graffiti.

“A muralist is an artist and has our respect,” Doria said in an interview this month, highlighting his plans to commission new works of street art. “Pichação is aggression … It is not a social problem. It is mental, criminal.”

Doria says police have caught more than 100 people writing on walls illegally in Sao Paulo since he took office in January.

He has established a fine for pichação of up to 10,000 reais ($3,200), or 10 times Brazil’s monthly minimum wage. But practitioners, known as ‘pichadores’, say that will do little to dissuade them from climbing high-rises and highway overpasses to leave their mark.

“What other artist puts their safety at risk for what they do?” said the pichador known as Du.

“All art involves freedom of expression, but pichação is the expression of freedom. You’re telling the world, ‘Here I am. You can’t ignore me.'”

Most pichadores write little more than their street name or the name of their crew, and spare social commentary in rare instances. “Who is Doria?” one scrawled in a tag.

Pichadores often compete for the highest or most audacious tags, but few would deface another’s work. Although it is synonymous with urban decay, those who take part say pichação has no ties to gangs in Sao Paulo.

Some in the graffiti world question the distinction between other street art and pichação, which has been featured in the Berlin Biennale, at the Cartier Foundation in Paris and at Sao Paulo Fashion Week.

Originally inspired by heavy metal album covers of the 1980s, the cryptic calligraphy has won admirers in the global graffiti scene, including photographer Martha Cooper, who has documented the New York subculture for four decades.

“I’m a big fan of what they’re doing in Sao Paulo. They’ve invented their own alphabet,” said Cooper, who was introduced to the old guard pichadores on a recent visit to Brazil.

“It’s not acts of random vandalism at all,” she said. “It’s a way of making your environment your own.”

(By Nacho Doce; Writing by Brad Haynes; editing by Diane Craft)