If you’re British and don’t know much about grime, you’re in the minority.

The influence of the music genre has ballooned in the UK in the last year, and it’s on track to become as disruptive and powerful as punk.

By: Mykaell Riley Principal Investigator, Black Music Research Unit University of Westminster

In the last year, album sales of grime music have grown significantly faster than the total UK music market (93% vs 6%) and the number of grime events on sale through Ticketmaster and Ticketweb has quadrupled since 2010.

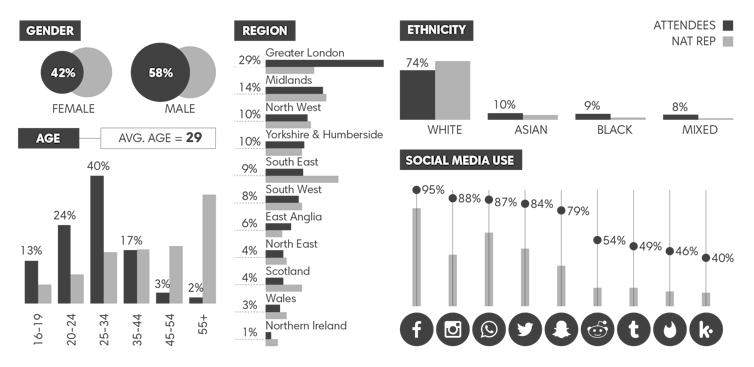

Our new study into the public reception of grime music found that 73% of Brits are aware of grime, with 40% having listened to it at some point.

In line with this trend, between this award season and the last, the genre has attracted more red carpet appearances, awards and accolades than any other.

We’ve also witnessed the usual grime attire of baseball caps and designer tracksuits become more interchangeable with dinner jackets and bow ties.

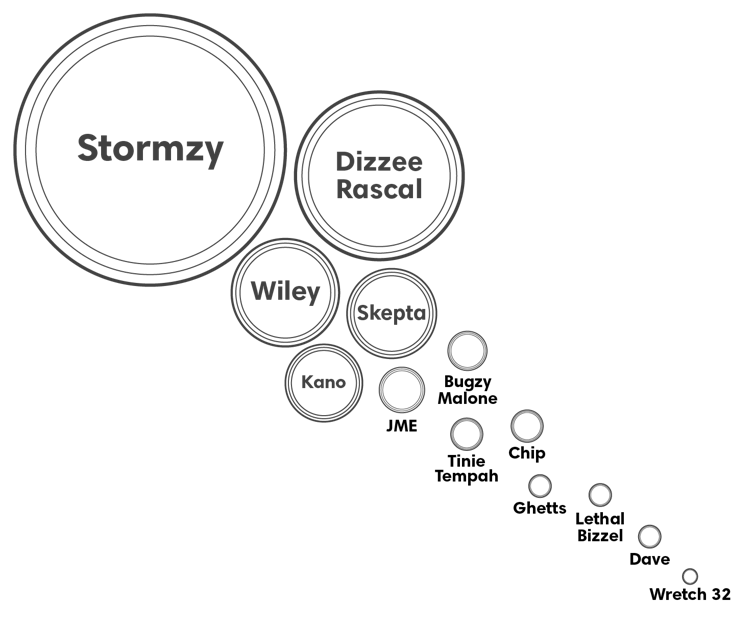

And why not, if you can have your brand enhanced by Emporio Armani (in the case of Dizzee Rascal), or feature on the front cover of GQ magazine (as did Stormzy).

For the first time, our research corroborates these claims.

We surveyed 2,000 grime fans and 58% of these said they voted for Labour during the 2017 election, with one-in-four (24%) saying that the #Grime4Corbyn campaign influenced their vote. It’s clear that #Grime4Corbyn gave a voice to the younger generation and influenced the way they voted.

Those more familiar with the genre will know that this success is hard-won and reflects the efforts of an underground, predominantly black British music community, that has pioneered this scene since the early 2000s and beyond.

Back then, in the bedrooms of East London council estates, the next generation of young producers and MCs were creating a brutal, edgy, uncompromising music. It was the sound of social deprivation emerging from the shadows of reurbanization and gentrification.

Leap forward to the present and the genre once dubbed the sound of London’s social underclass has blossomed. With its successes in both the singles and album charts, its arrival on the festival circuit and its growing international following, grime continues to defy industry assessments of its potential.

This is why it still could provoke the most disruptive cultural transformation of the British music industry since punk. With the leading names now regulars on the festival circuit and capable of packing London’s Wembley or the O2, grime has verified its credentials.

Grime still has some distance to travel with regards to its international profile but within the UK, it has already secured recognition from the music industry as the most successful black British music genre – and not unlike punk, transformed perceptions and approaches to popular music.

Live shows have also transformed ideas about grime’s audience, often seen jostling and bumping into each other in response to the performance. At early gigs, primarily attended by young black men in small venues, this activity would have been described as aggressive and potentially violent. But today, at larger venues and festivals and with it’s change of audience it’s more likely to be described as “moshing”.

So the tide, it seems, has turned.

Or has it?

Grime is still struggling to transform negative perceptions within the London Metropolitan Police force, who use the controversial Form 696.

This is a risk assessment form that is applied solely to events that “predominantly feature DJs or MCs performing to a recorded backing track” – and is therefore seen by many as discriminatory.

It has been used by the police to shut down a number of grime events on the grounds of “public safety,” negatively impacting on the income streams of performers and promoters alike.

Nonetheless, in 2017, grime demonstrates the promise of a complex and diverse music industry. It also shows that a journey fuelled by enterprise, entrepreneurialism and creativity has the potential to overcome such lingering negative perceptions to achieve even greater things.

Mykaell Riley, Principal Investigator, Black Music Research Unit, University of Westminster

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.