American hip-hop group, The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy, first graced my ears in late 1992. It was thanks to my housemate in undergraduate school who was an indie music fan. He knew I was a hip-hop head, and made no hesitation in excitedly playing me The Disposable Heroes’ first album, Hypocrisy is the Greatest Luxury.

As the opening song launched, I scanned the track list on the CD case – “Language of Violence”, “Socio-Genetic Experiment” and the globally significant “Television, the Drug of The Nation”, were some of the song titles. I realised I could be witnessing the rise of another politically charged great to follow in the footsteps of the incredible Chuck D, who led the powerful, socially-conscious hip-hop group Public Enemy.

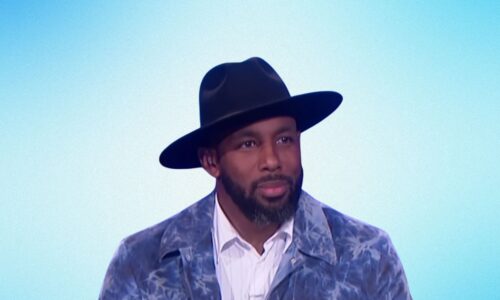

The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy appealed to indie-rock kids as much – if not more so – than hip-hoppers though. It was largely due to their electronica driven dubbed-out sonics and guitar soundscapes but also their previous incarnation as post-punk industrial rock band The Beatnigs. Yet the political strength in frontman Michael Franti’s rapping resonated with the sound of early 1990s hip-hop in flow and eloquence, and on no song is his vocal quality greater than “Positive”.

Political messages

Released in 1992 on the B-side of “Famous and Dandy (Like Amos ‘n’ Andy)”, the song “Positive” seemed to slip by the great political messages of Franti, yet was particularly poignant for the time. And while they were an American band, their songs were universal and had an impact across the world.

The narrative in “Positive” centres on a tormented soul as he deals with the angst of awaiting an HIV test result, and follows his train of thought as he weighs up the reality of being HIV positive.

Franti’s subdued delivery symbolised a state of shock and emptiness as the protagonist attempts to reconcile with ex-partners, make sense of his situation and consider his future. All the while the band jams a backdrop of smoked-out funk and blues-infused harmonica riffs, adding to the song’s atmospherics as it builds the serendipitous story.

The protagonist has fallen in love, and agrees to undertake an HIV test for his and his love’s peace of mind, and here is where the skeletons in the closet begin to rattle:

If I love you, then I better get tested

Make sure we are protected

I walk through the park dressed like a question mark

Hark! I hear my memory bark

In the back of my brain

Makin’ me insane, like cocaine.

His recurring thoughts “How am I gonna live my life if I’m positive? Is it gonna be a negative?” are far from rhetoric, and eek through the calm jazz-funk fuelled music in each chorus. In verse two, he approaches the clinic and nerves play on his past existence, and reflects:

About all the time that I neglected

Making sure that I was protected

They took my blood with an anonymous number

Two weeks waitin’ and wonderin’.

In the weeks following the test, the long wait for the results induces a rising fear as the protagonist attempts to reassure himself:

I go home to kick it in my apartment

I try to give myself a risk assessment

The waiting is what can really annoy ya

Every single day is more paranoia.

Unable to bear the wait, he teaches himself about the virus to kill time, and slowly counts through the plethora of past lovers he’s had sexual contact with:

I’m readin’ about how AIDS gets transmitted

Some behaviour I must admit it

Who I slept with, who they slept with

Who they, who they, who they, who they slept with.

This song is more than a protest. It deals with the prejudices surrounding HIV and AIDS as well as having an educational angle.

The song was revisited in 1994 after Franti formed his new band Spearhead. It was released as the fourth single from Spearhead’s debut album Home. With added female backing vocals and a much smoother delivery on Franti’s part the song feels toned down – yet its significance is underscored through its remaking.

Leading cause of death

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) first made global headlines in the early 1980s, and the American-based Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that by 1993, HIV had become the leading cause of death for young African American men. And it wasn’t unique to the US.

At the root of these shocking statistics was education. In 1993 on the outro to the track, “Midnight”, by American hip-hop group A Tribe Called Quest, the digitised “tour guide” states:

Did you know that the rate of AIDS in the black and Hispanic community is rising at an alarming rate? Education is the proper means for slowing it down.

The stigma and misunderstanding attached to HIV and AIDS has improved since the turn of the millennium. In 2007 Rattani, Syed and Sugarman demonstrated that the positivity about HIV in hip-hop lyrics has improved and:

despite the conspiratorial views towards HIV/AIDS in hip-hop lyrics, nearly twice as many lyrics were found providing a strong and overwhelmingly positive collection of messages related to HIV/AIDS prevention.

This is a big step forward, but appears to have fallen off the subject agenda in the past decade. 36.7 million people worldwide are currently living with HIV/AIDS, and over 2.1 million of them are children. Hip-hop can and should be at the forefront of HIV/AIDS education, and songs like “Positive” still have the educational values needed to reduce the prevalence of HIV and AIDS, which sadly continues to thrive.![]()

Adam de Paor-Evans, Principal Lecturer in Cultural Theory / Research and Innovation Lead, School of Art, Design and Fashion, Faculty of Culture and the Creative Industries, University of Central Lancashire

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.